The Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (TPNW)

What is the TPNW?

The TPNW is a landmark United Nations (UN) treaty that seeks to universally prohibit countries from developing, testing, producing, acquiring, possessing, stockpiling, using or threatening to use nuclear weapons. As well, the Treaty prohibits countries from deploying these weapons on national territory, and assisting another country from partaking in any prohibited actions. Importantly, the TPNW includes provisions to assist nuclear weapons victims and attempt to clean the environment from the harmful radiation exposure released by the production, testing and use of nuclear weapons.

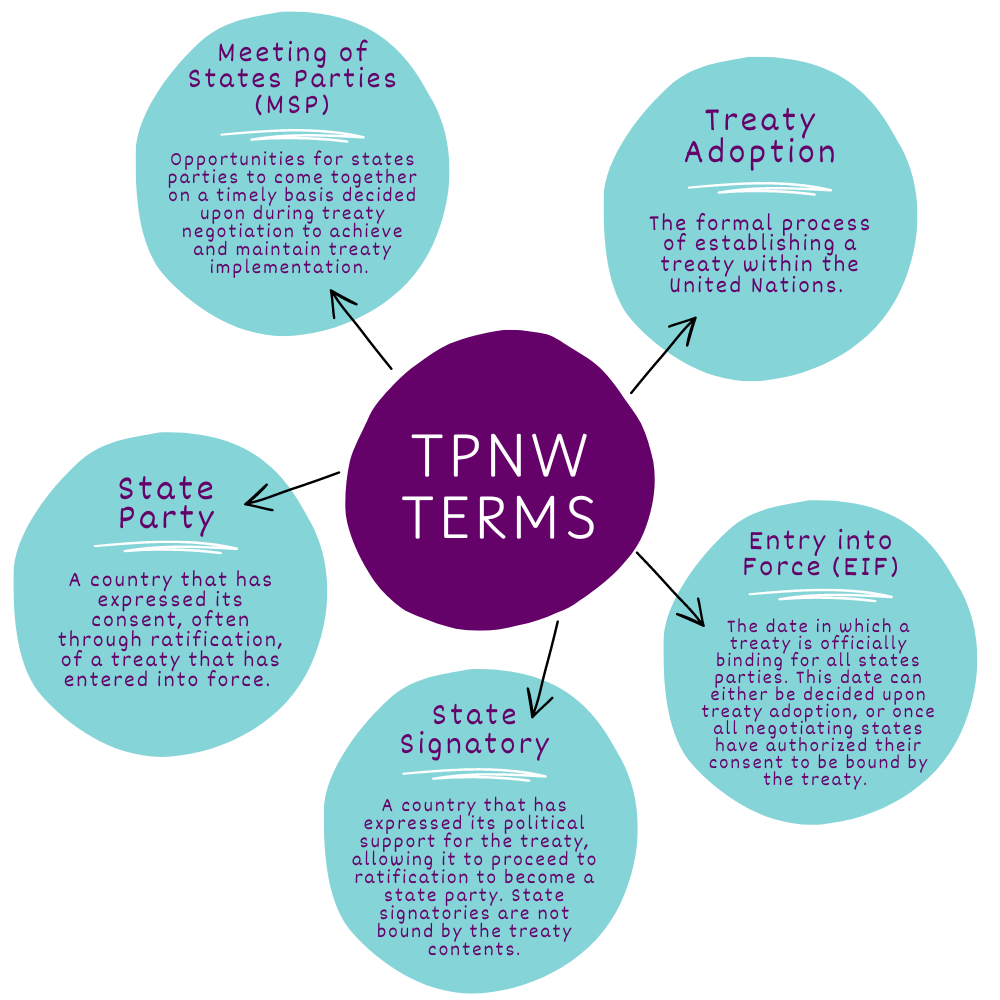

The Treaty was adopted by the United Nations on July 17, 2017 and opened for state signature about two months later, on September 20, 2017. After three years of determined advocacy and organizing by Treaty supporters to achieve the state-signature threshold (50 nations) for ratification, the TPNW entered into force on January 22, 2021.

Currently, 93 nations have signed the treaty, and of these, 70 countries have also ratified the TPNW becoming a Party to the Treaty. None of the countries that possess nuclear weapons have signed or ratified the Treaty, claiming that the Treaty undermines the longstanding Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons (NPT), which is the cornerstone of the global nuclear nonproliferation regime. In reality, the TPNW does not undermine the NPT, but rather bolsters it by strengthening the commitments of Article VI in the NPT that call for nuclear disarmament and a robust nuclear disarmament regime. TPNW goes further: it creates a structure and accountable legal processes for any state to declare itself nuclear-free, and for any nuclear weapons-state to disarm under its formal jurisdiction.

The TPNW is silent on nuclear energy, except to state that nothing in its provisions pertains to nuclear energy. It is the hope of many Indigenous and other local communities impacted by uranium mining and nuclear waste disposal that originate today from both the production of nuclear weapons and nuclear energy that the TPNW will someday be widened. Ending all industrial markets and use for uranium is a goal of many of these communities.

Treaty Origins

Unknown to many, nuclear weapons are the only weapon of mass destruction not totally banned. Both biological and chemical weapons have been banned for decades, with biological weapons reaching their demise by 1975 and chemical weapons following suit more than 25 years later, in 1997. The 1997 Anti-Personnel Mine Ban Treaty, commonly referred to as the Mine Ban Treaty, and the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions further illustrated that the world is capable of banning horrific weapons to protect people and the planet.

When the NPT was introduced in 1968 and entered into force just two years later, it was lauded as a major global achievement. Not only did it commit the majority of the world to not seek a nuclear arsenal, it also committed the original nuclear weapons states -- the U.S., U.K., France, Russia and China -- to eventual disarmament. However, by 2010, 40 years after the NPT entered into force, non-nuclear weapons states around the world were frustrated with the nuclear weapons states for making very little progress on their commitments under Article VI of the Treaty to work to disarm. Mary Olson was invited several times to various UN events to share her research on ionizing radiation, nuclear weapons, and nuclear energy. On one such occasion, the 2010 Review Conference for the NPT, Mary’s presentation focused on community and health impacts of uranium mining and processing for nuclear fuel in a paper coauthored by 19 other nuclear advocates and experts indirectly encouraged support for the 2010 NPT Review Conference including humanitarian language in its concluding report. The inclusion of a phrase about humanitarian impacts enabled a long-term strategy to unfold: the NPT is a military treaty, and therefore under the jurisdiction of the UN Security Council. The UN General Assembly (it is essentially a bi-cameral organization) is where matters of humanitarian law are conducted. Nuclear, up to that point, had been seen as strictly military.

A year later, the International Committee of the Red Cross renewed its strong voice on nuclear disarmament when it adopted a resolution that called for all nations to negotiate an international agreement that was legally binding and would totally ban nuclear weapons. And in 2013, the three-part Humanitarian Impact Conferences began. These conferences -- set in Oslo, Norway in March 2013, Nayarit, Mexico in February 2014 and Vienna, Austria in December 2014 -- focused on the short- and long-term humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons.

Mary’s 2011 paper entitled Atomic Radiation is More Harmful to Women, revealed the significantly disproportionate impacts of ionizing radiation released by the detonation of a nuclear weapon, on young girls, women and the elderly. Someone within the Conferences discovered her paper, and invited her to the third Humanitarian Impact Conference in Vienna. Yet again, Mary’s expertise proved invaluable. The evidence she presented enabled the case to be made that nuclear weapons fit the template for humanitarian jurisdiction. Her simple silhouette figures showing girls harmed more than boys and women harmed more than men (measured as cancer incidence over 60 years) allowed disarmament supporters in and outside the UN to make a strong case for establishing a nuclear disarmament treaty in the UN, under the General Assembly and the humanitarian code.

The outcome of the Humanitarian Impact Conferences was 125 countries pledging to create a humanitarian treaty that totally banned nuclear weapons. This Humanitarian Initiative transformed into a treaty proposal that was presented to the UN General Assembly in 2016 to vote to take the next step of negotiating an actual nuclear ban treaty. That vote passed, and by July 2017 the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons had been drafted by a special treaty conference and then presented to the UN General Assembly for a vote where it was overwhelmingly adopted by 122 nations.

Positive Impacts of the TPNW

Later, Mary met with an ambassador in Brussels who informed her that her research and her paper were crucial in helping to pave the way for the TPNW. Previously, it was thought that nuclear weapons had a completely indiscriminate nature, meaning they impacted everyone everywhere equally. Therefore, it was nearly impossible to make the case that the use of nuclear weapons had any direct (disproportionate) humanitarian impacts. The goal was to find a legal basis for their prohibition under the jurisdiction of the General Assembly, like the extremely successful 1997 Mine Ban Treaty. Mines (land and water) are now completely banned. Those horrific weapons had been killing civilians for decades after they were planted in conflict zones like Cambodia and Laos during the Vietnam War.

However, Mary’s paper solved that problem. She re-analyzed research that focused on the human health impacts from the initial pulse of gamma and neutron radiation released by the detonation of the bomb, and the subsequent long-term consequences of this radiation exposure for the survivors of the US nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Through her re-analysis, Mary found that women, young girls, and the elderly are all more vulnerable to the harms of radiation exposure than their male counterparts.

These monumental findings showed clear humanitarian impacts, not only from the aftermath of a nuclear exchange, but also from the immediate use of nuclear weapons. This finding created the basis for creating a nuclear disarmament treaty under humanitarian law, like the Mine Ban Treaty, and not military law like the NPT. This meant that the Treaty, if adopted and entered into force, would be under control of the UN General Assembly, where there was no veto power and every nation has one vote, and decisions are made by a simple majority. This is in contrast to the Security Council, whose five permanent members are all nuclear powers -- the U.S., Russia, France, China, and the U.K.-- and have the power to veto anything they don’t support.

This is important because if the TPNW were written in accordance with military law, it would have been voted upon by the Security Council, where it would have inevitably failed considering the makeup of the Council. However, since the TPNW, with the help of Mary’s research, was written in accordance with humanitarian law, it meant the General Assembly -- where non-nuclear weapons states who were long frustrated with the lack of progress on nuclear disarmament had as much of a voice as the Security Council Members -- was responsible for voting on the adoption of such a treaty. Therefore, when it came time to vote on adopting the now fully-formed TPNW in July 2017, 122 nations voted to adopt this landmark treaty, officially laying the groundwork to build a new world, free from the threat of nuclear weapons.

Another positive impact of the TPNW is in the way it was negotiated, and how that subsequently influenced the contents of the Treaty to include provisions calling for robust systems of victims assistance and environmental remediation. Nuclear weapons victims and civil society members were heavily involved in the creation of the TPNW. This allowed for more complex and accurate conversations on the health and environmental impacts of nuclear weapons, and the level of assistance and resources required to support victims and restore the environment. Only three other UN treaties have been negotiated in such a manner, with the intended population the Treaty seeks to protect intimately involved in the formation of the treaty, and provisions included to effectively support these marginalized populations -- those treaties are the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions.

How Can You Help Ban Nuclear Weapons?

Mary’s journey proves that anyone has the power to help build a world free from nuclear weapons. GRIP has always been about trying to inform as much of the public as possible on the dangers of radiation exposure, and to support further expansion of our knowledge about radiation impacts. One way to help the movement to ban nuclear weapons is to support GRIP’s work.

There are many organizations, coalitions, communities and individuals working to universalize the TPNW. There is no greater champion of the TPNW than the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN). Founded in 2007, to establish a legally binding treaty to ban nuclear weapons, ICAN played a critical role in the creation and adoption of the TPNW, receiving the 2017 Nobel Peace Prize for their tireless work. Now that the Treaty has entered into force, ICAN has turned its attention to getting the countries that haven’t ratified the TPNW yet to do so, especially the nine nuclear powers through its public ICAN Cities Appeal and ICAN Parliamentary Pledge campaigns, as well as the divestment work via the Don’t Bank on the Bomb campaign. Each campaign seeks to encourage cities and country officials respectively to urge their own national government to join the Treaty. Anyone can and is encouraged to take part in the campaigns.

Resources

To learn more about the TPNW, take a look at the resources below.

WEBSITES

United Nations Office on Disarmament Affairs TPNW Treaty Page

International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN)

Visit the RESOURCES Section of this website

REPORTS/GUIDES

Humanitarian Impact and Risks of Nuclear Weapons | ICAN

A pocketbook guide created by ICAN sharing the humanitarian impact and risks of nuclear weapons. NOTE: This was created in 2016, so while some information may be outdated the core messages remain the same.

Common Misconceptions of a Ban Treaty | ICAN

A pocketbook guide created by ICAN outlining the common misconceptions on a nuclear ban treaty and messaging guidance to respond. NOTE: This was created in 2016, so while some information may be outdated the core messages remain the same.

The origins and influence of victim assistance: Contributions of the Mine Ban Treaty, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities and Convention on Cluster Munitions | International Review of the Red Cross

Authors Bonnie Docherty and Alicia Sanders-Zakre discuss the history of victim assistance in international treaties through the 1997 Mine Ban Treaty, the 2006 Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, and the 2008 Convention on Cluster Munitions, and lay out how the TPNW has followed in the footsteps of these landmark treaties.

A chapter of a UNODA report that analyzes the importance of comprehensive humanitarian action to redress the many health harms as a result of exposure to ionizing radiation.

ARTICLES

“The false equivalency of nuclear disarmament and nuclear abolition” | Jasmine Owens

“The Future of Arms Control Lies in the Nuclear Ban Treaty” | Melissa Parke

“Nuclear deterrence is the existential threat, not the nuclear ban treaty” | Ivana Nikolić Hughes, Xanthe Hall, Ira Helfand, and Mays Smithwick

“The UN Nuclear Ban Treaty is Leading Resistance to Nuclear Autocracy” | Robert Rust

“Addressing Verification in the Nuclear Ban Treaty” | Zia Mian, Tamara Patton, and Alexander Glaser

MOVIES/VIDEOS

Mary Olson presentation at side event of 2015 NPT Review Conference

PODCASTS

Unveiling Radiation's Hidden Dangers with Mary Olson | The DNA of Things